One of the perks of academia is the thrill of presenting results, thoughts and ideas at international conferences. Although the best meetings often fall at the busiest moment in the teaching semester and the travel can be tiring, there is no doubt that interacting directly with one’s peers is a huge shot in the arm for any researcher – not to mention the opportunity to travel to interesting locations and experience different cultures.

![IMG_2009[1]](https://antimatter.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/img_20091.jpg?w=598&h=598)

The view from my hotel in San Sebastian this morning.

This week, I travelled to San Sebastian in Spain to attend the Third International Conference on the History of Physics, the latest in a series of conferences that aim to foster dialogue between physicists with an interest in the history of their subject and professional historians of science. I think it’s fair to say the conference was a great success, with lots of interesting talks on a diverse range of topics. It didn’t hurt that the meeting took place in the Palacio Mirimar, a beautiful building in a fantastic location.

The Palacio Mirimar in San Sebastian.

The conference programme can be found here. I didn’t get to all the talks due to parallel timetabling, but three major highlights for me were ‘Structure or Agent? Max Planck and the Birth of Quantum Theory’ by Massimiliano Badino of the University of Verona, ‘The Principle of Plenitude as a Guiding Theme in Modern Physics’ by Helge Kragh of the University of Copenhagen, and ‘Rutherford’s Favourite Radiochemist: Bertram Borden’ by Edward Davis of the University of Cambridge.

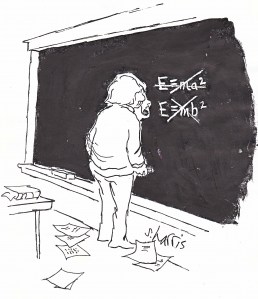

![IMG_2014[1]](https://antimatter.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/img_20141.jpg?w=573&h=763)

A slide from the paper ‘Max Planck and the Birth of Quantum Theory’

My own presentation was titled ‘The Dawning of Cosmology – Internal vs External Histories’ (the slides are here). In it, I considered the story of the emergence of the ‘big bang’ theory of the universe from two different viewpoints, the professional physicist vs. the science historian. (The former approach is sometimes termed ‘internal history’ as scientists tend to tell the story of scientific discovery as an interplay of theory and experiment within the confines of science. The latter approach is termed ‘external’ because the professional historian will consider external societal factors such the prestige of researchers and their institutions and the relevance of national or international contexts). Nowadays, it is generally accepted that both internal and external factors usually often a role in a given scientific advance, a process that has been termed the co-production of scientific knowledge.

![IMG_2022[1]](https://antimatter.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/img_20221.jpg?w=543&h=407)

Giving my paper in the conference room

As it was a short talk, I focused on three key stages in the development of the big bang model; the first (static) models of the cosmos that arose from relativity, the switch to expanding cosmologies in the 1930s, and finally the transition (much more gradual) to the idea of a universe that was once small, dense and hot. In preparing the paper, I found that the first stage was driven almost entirely by theoretical considerations (namely, Einstein’s wish to test his newly-minted general theory of relativity by applying it to the universe as a whole), with little evidence of co-production. Similarly, I found that the switch to expanding cosmologies was driven by almost entirely by developments in astronomy (namely, Hubble’s observations of the recession of the galaxies). Finally, I found the long rejection of Lemaître’s ‘fireworks’ universe was driven by obvious theoretical problems associated with the model (such as the problem of the singularity and the age paradox), while the eventual acceptance of the model was driven by major astronomical advances such as the discovery of the cosmic microwave background. Overall, my conclusion was that one could give a reasonably coherent account of the early development of modern cosmology in terms of the traditional narrative of an interplay of theory and experiment, with little evidence that social considerations played an important role in this particular story. As I once heard the noted historian Hasok Chang remark in a seminar, ‘Sometimes science is the context’.

Can one draw any general conclusions from this little study? I think it would be interesting to investigate the matter further. One possibility is that social considerations become more important ‘as a field becomes a field’, i.e., as a new area of physics coalesces into its own distinct field, with specialized journals, postgraduate positions and undergraduate courses etc. Could it be that the traditional narrative works surprisingly well when considering the dawning of a field because the co-production effect is less pronounced then? Certainly, I have also found it hard to discern any major societal influence in the dawning of other theories such as special relativity or general relativity.

Coda

As a coda, I discussed a pet theme of mine; that the co-productive nature of scientific discovery presents a special problem for the science historian. After all, in order to weigh the relative impact of internal vs external considerations on a given scientific advance, one must presumably have a good understanding of each. But it takes many years of specialist training to attempt to place a scientific advance in its true scientific context, an impossible ask for a historian trained in the humanities. Some science historians avoid this problem by ‘black-boxing’ the science and focusing on social context alone. However, this means the internal scientific aspects of the story are either ignored or repeated from secondary sources, rather than offering new insights from perusing primary materials. Besides, how can one decide whether a societal influence is significant or not without considering the science? For example, Paul Forman’s argument concerning the influence of contemporaneous German culture on the acceptance of the Uncertainty Principle in quantum theory is interesting, but pays little attention to physics; a physicist might point out that it quickly became clear to the quantum theorists (many of whom were not German) that the Uncertainty Principle arose inevitably from wave-particle duality in all three formulations of the theory (see Hendry on this for example).

Indeed, now that it is accepted one needs to consider both internal and external factors in studying a given scientific advance, it’s not obvious to me what the professionalization of science history should look like, i.e., how the next generation of science historians should be trained. In the meantime, I think there is a good argument for the use of multi-disciplinary teams of collaborators in the study of the history of science.

All in all, a very enjoyable conference. I wish there had been time to relax and have a swim in the bay, but I never got a moment. On the other hand, I managed to stock up on some free issues of my favourite publication in this area, the European Physical Journal (H). On the plane home, I had a great read of a seriously good EPJH article by S.M. Bilenky on the history of neutrino physics. Consider me inspired….

![IMG_2009[1]](https://antimatter.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/img_20091.jpg?w=598&h=598)

![IMG_2014[1]](https://antimatter.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/img_20141.jpg?w=573&h=763)

![IMG_2022[1]](https://antimatter.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/img_20221.jpg?w=543&h=407)