I spent last weekend at the Frontiers of Physics conference at Trinity College Dublin. This is an annual meeting hosted by the Institute of Physics in Ireland; the aim is to establish links with secondary schools all over the country and to present the latest developments in physics and physics teaching. This year it was Trinity’s turn to host the conference and it was excellent, not least due to the superb organisation of IoP teaching coordinators Paul Nugent and David Keenahan.

Saturday morning featured some great lectures in the historic Schrödinger lecture theatre, located in the Fitzgerald building of Trinity’s School of Physics. Visiting this building always feels like coming home for me, as I did my PhD in one of the labs downstairs and gave tutorials in the Schrödinger theatre as a postgrad. The library on the second floor of the Fitzgerald building is becoming a notable science museum, with exhibits for many great scientists associated with Trinity such as Preston, Joly, Fitzgerald and Walton. (Schrödinger himself was a Professor at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, not Trinity, but the theatre is named after the famous ‘What is Life? ‘ series of public lectures he gave there there).

The Schrödinger lecture theatre on the top floor of the Fitzgerald building

The Fitzgerald building, home to the physics department at TCD. The bubbles are a mockup of a sculpture that will honour the department’s Nobel laureate Ernest Walton

I won’t describe the lectures in detail, but three stood out for me: ‘Tuning in the radio sun’, a description of solar astronomy at Birr Castle by Prof Peter Gallagher, head of the solar physics group at Trinity: ‘Tiny but mighty’ , a superb introductory lecture on nanotechnology by Prof Jonathan Coleman, head of the low-dimensional nanostructures group at Trinity: and ‘CERN, the LHC and the Higgs boson’ by Steve Myers, director of accelerators and technology at CERN.

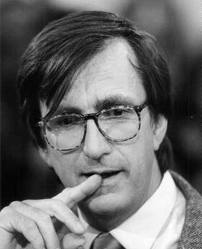

Yes, that Steve Myers, the Belfast-born director of accelerators at CERN. Steve gives great talks on the nuts-and-bolts of the Large Hadron Collider and this was the main reason I was at the meeting. I’m scheduled to give yet another talk on the Higgs boson next month, so it’s important to catch lectures like this whenever I can. There’s nothing like hearing details of the experiment from the horse’s mouth and Steve certainly didn’t disappoint.

Steve Myers in action at the conference

On the teaching of physics, Dr Karen Bultitude of University College London gave an interesting lecture on ‘Gender Aware Teaching Practice’. As everyone in the discipline knows, a marked gender imbalance persists amongst students choosing physics; Karen’s main point was that all of the research done in this area indicates that making physics more ‘girly’ simply does not work, and she had some important tips for making physics more approachable for both genders. (Once more, it raises the question how a certain video at the European Comission ever saw the light of day, but let’s not go there).

After the lectures, we were treated to lunch in Trinity Dining Hall; I think those who had not visited the college before were blown away by the Hall and by the walk across Front Square. Maybe I notice this sort of thing more after another trip to the US (see previous post), but the best was yet to come..

The Dining Hall at Trinity

Front Square at Trinity College

After lunch, we were treated to an exhibition of Walton memorabilia by Dr Eric Finch. (Ernest Walton, a former Head of Physics at Trinity, won a Nobel prize for splitting the atomic nucleus with Cockroft in 1932). Eric had many fascinating things to show us, not least the famous letter where the brilliant young scientist describes his ‘red-letter day’ to his fiancee. Best of all, the exhibition is currently situated in Trinity’s Long Room, one of the most famous libraries in the world and a sight well worth seeing in it’s own right.

Dr Eric Finch at the Walton exhibit in the Long Room

The Long Room at TCD – it really is like this

Finally, we all trooped back to the physics department to see the Monck observatory. Since my time at the college, an observatory has been installed on the roof of the Fitzgerald building, consisting of an Atmospheric and Space Weather Monitor (outside radio antenna) and a Schmitt reflecting telescope (inside the dome, see below). Brian Espey, Professor of astrophysics at TCD, described the operation of the telescope and we each had a peep. The observatory must be one of the most centrally located telescopes anywhere in the world- however, apparently the light pollution is not as bad as you might expect because the college is a quiet island in the centre of the city at night. I’m told the main problem is the use of floodlights for rugby practice!

The new dome on top of the Fitzgerald building

The Schmitt reflector inside the dome

The radio antenna for atmospheric measurements

All in all, a great meeting in a superb setting. The Frontiers conference takes place in a different venue each year, but it’s hard to compete with 400 years of history…