RTE radio recorded an interview with me today on the subject of Stephen Hawking. I’m told it’s to have on file so I trust they don’t know something I don’t! Whatever the reason, it’s nice to have the opportunity to pay tribute to a living legend. Below is a script I prepared the interview; we only used a small part.

******************************************************************************

Q: Who is he?

Stephen Hawking is a famous English physicist at Cambridge University known for his work in cosmology, the study of the universe. In particular, he is admired for his work on black holes and on the big bang model of the origin of the universe.

Q: Why is he so famous?

Einstein used to be the only famous scientist of modern times, but Stephen Hawking has inherited that role. I like to think that one reason is his field of study; there seems to be a public fascination with scientific concepts such as the big bang and the nature of space and time (it’s hardly a coincidence that much of Einstein’s work was in this field).

Another reason may be Hawking’s disability. He was diagnosed with motor neuron disease (ALS) in his early 20s and given two years to live. The story of a brilliant mind trapped in a crippled body has universal appeal, and the wheelchair-bound figure communicating deep ideas by voice synthesizer has become an icon of science.

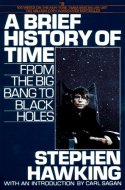

Then there’s the book. In the 1980s, Hawking published A Brief History of Time, a book on the big bang aimed at the general public – it quickly became an unprecedented science bestseller and made him a household name. Since then, he has devoted a great deal of time to science outreach, unusual for a scientist at this level.

Q: Where is he from?

He was born in London in 1942, the son of two academics, and studied physics at Oxford. He wasn’t outstanding as an undergraduate but he did well enough to be accepted for postgraduate research in Cambridge. There, he became interested in cosmology, in particular in the battle being waged at Cambridge between the ‘big bang’ and ‘eternal universe’ theories. He showed early promise as a postgraduate when he demonstrated that Fred Hoyle, a famous cosmologist and prominent exponent of the eternal universe, had made a mathematical error in his work.

Q: Can you say a little about Hawking’s science?

His work is focused mainly on phenomena such as black holes and the big bang. Such phenomena are described by Einstein’s theory of relativity, which predicts that space and time are not fixed but affected by gravity. (In the case of black holes, relativity predicts that space is so distorted by gravity that energy,even light, cannot escape. In the case of the universe at large, relativity predicts that our universe started in a tiny, extremely hot state and has been expanding and cooling ever since; the so-called big bang model).

However, relativity does not work well on very small scales; this is the realm of quantum physics. Hawking’s lifelong work concerns the attempt to obtain a better picture of the universe by combining relativity (used to describe space and time) with quantum physics (used to describe the world of the very small).

He first established his reputation by defining the problem; with the mathematician Roger Penrose, he showed that relativity predicts that, under almost all conditions, an expanding universe such as our own must begin in a singularity i.e. a point of infinite density and temperature. This is not physically realistic and suggests that relativity on its own does not provide a true picture of the universe.

In later work, Hawking focused on black holes (a black hole is something like a big bang in reverse and may therefore offer clues to the puzzle of the origin of the universe). Successfully combining general relativity with quantum physics for this special case, Hawking was able to predict that black holes are not entirely black; instead they emit some energy in the form of radiation, now known as Hawking–Bekenstein radiation. Most physicists are convinced by the logic and beauty of this result but Hawking radiation will be difficult to measure experimentally as it is predicted to be extremely weak.

My favourite Hawking contribution is the no-boundary universe. Working with James Hartle, he used a combination of relativity and quantum physics to predict that our universe may not have had a definite point of beginning because time itself may not be well-defined in the intense gravitational field of the infant universe!

Q: Is Hawking another Einstein?

No. Einstein made a great many contributions to diverse areas of physics. Also, relativity fundamentally changed our understanding of space and time, with profound implications for all of science and philosophy.(For example, the big bang model is merely one prediction of relativity). It’s hard for any scientist to compete with this.

Q: Why has Hawking not been awarded a Nobel prize?

He has received many prestigious awards, but not a Nobel. It’s quite difficult for a modern theoretician to win the prize because Nobel committees put great emphasis on experimental evidence. While we now have strong evidence that black holes exist, Hawking radiation will be very difficult to detect as it is predicted to be extremely weak.

Q; What is he working on these days?

At a conference in Dublin a few years ago, Hawking suggested a possible solution to the information paradox, a controversy over whether information is lost in black holes. The jury is still out on his solution. He is also involved with the theory of the cyclic universe, a theory that suggests there many have been many bangs.

Q: What lies in the future for Hawking?

Who knows. Last month, he celebrated his 70th birthday with a prestigious conference at Cambridge, 50 years after his terminal diagnosis. However, he was too ill to attend in person, reviving fears about his health. For now, he continues to work as ever, defying the predictions of modern medicine…

P.S. What’s all this about Hawking and God?

A Brief History of Time famously concludes with the phrase ‘‘..and then we would know the mind of God’’. At the time, many commentators interpreted this statement to mean that Hawking was religious. However, he was being mischievous – it is clear from other writings that he is not a believer in the normal sense. Indeed, his most recent book, The Grand Design, provoked controversy by stating that ‘‘It is not necessary to invoke God to set the universe going.” This statement was interpreted widely as a dismissal of God – in fact, it reflects standard cosmology (something can indeed arise from ‘nothing’) and says nothing about the existence of God.