This week is Science Week in Ireland, with science events taking place all over the country. There are talks and demonstrations on every aspect of science you can think of, from a demonstration of animal magic at Killaloe in County Limerick to astronomy at the Crawford Observatory of University College Cork.

This evening, I will give a public lecture on the Big Bang in Trinity College, hosted by Astronomy Ireland. We’re still in the International Year of Astronomy, celebrating the 400th anniversary of Galileo’s use of the telescope to establish the heliocentric model of the solar system, so it’s highly appropriate to have a lecture describing another paradigm shift in science brought to us by astronomy: the discovery of the expanding universe and the big bang model that followed. I’m delighted to be giving the lecture as Astronomy Ireland do a fantastic job of promoting astronomy and science around the country, with night-classes in astronomy, public viewings of astronomical events and regular public science lectures. It’s also fun to tell the story of the discovery of the big bang model to people with an interest in astronomy, as many of them already know most of the facts, but from a slightly different perspective. Indeed, much of what we know of cosmology really comes from astronomical observation. You can find a poster, a summary of the lecture and the slides I will use here.

As I write this post, I’m sitting in the RTE canteen having done an interview promoting the lecture on Today with Pat Kenny, the flagship radio show of RTE, the Irish broadcasting corporation. (The last time I was at RTE I was auditioning for deputy work with the Concert Orchestra but that’s another story!). I think the interview went well, it was certainly good fun. Unlike a lot of scientists I quite enjoy talking to the media, it’s a challenge getting deep ideas across in a short interview without sounding completely incomprehensible! I also find this particular radio show very good and listen in whenever I can.

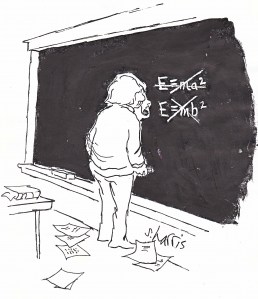

Astronomy Ireland marketed the lecture as ‘The Big Bang: Was Einstein Wrong? which is quite a good hook, so the interview touched on this quite a bit. Of course the answer is YES, it refers to a famous Einstein gaffe. When E. applied the general theory of relativity, his new theory of space, time and gravity, to the entire universe, it predicted a universe that was changing in time (space and time expanding). No evidence for such a thing existed at the time, so Einstein then introduced an extra term into the equations of relativity to force the universe to be static. Such fudge-factors are always risky in science and sure enough it turned out to be a big mistake. In 1929, the American astronomer Edwin Hubble established unequivocally that faraway galaxies are rushing away from one another and mathematicians realised that the universe is indeed expanding. Einstein immediately dropped the spurious term (known as the cosmological constant), declaring it his ‘greatest blunder’. You can listen to a podcast of the interview here, I hope I got the point across!

Einstein: right about relativity, but missed the prediction of the expanding universe

On Tuesday evening, I’ll give a repeat of the lecture in Waterford,in the main Auditorium of our college. On Wednesday, there is a talk on on the legacy of Charles Darwin at Waterford City Hall, which should be very good, I hope to attend myself. Both these lectures have been organised by CALMAST, the science communication group at WIT. All in all, it’s going be a busy week.

Update: I can see why media interviews are important, we had to change venue to the largest lecture theatre in trinity last night as we got a turnout of about 500! I think the lecture went well, I certainly enjoyed it.